How to keep human factors (HF) programs moving forward during the pandemic – Part 2 Remote Studies

How to keep human factors (HF) programs moving forward during the pandemic – Part 2 Remote Studies

In Part 1 of this 2-part series, we discussed considerations for in-person testing during the current pandemic climate. However, if in-person testing is not feasible due to local coronavirus rates and/or federal or state guidelines, companies may be interested in remote testing as an alternative. This newsletter covers several important advantages and disadvantages of remote testing for teams to consider when deciding whether to pursue this strategy.

As a reminder, Part 1 of this newsletter discussed the importance of adapting your HF strategy amidst the pandemic and included a discussion about adapting HF strategies and building contingencies into the HF timeline so your company has options ready given the dynamics of the pandemic at the given time. A variety of strategies may be leveraged to meet organizational HF goals, but their applicability will depend largely on the device and user population(s) being studied. In Part 2, we focus specifically on the remote testing strategy introduced in Part 1.

Why should you consider a remote HF study?

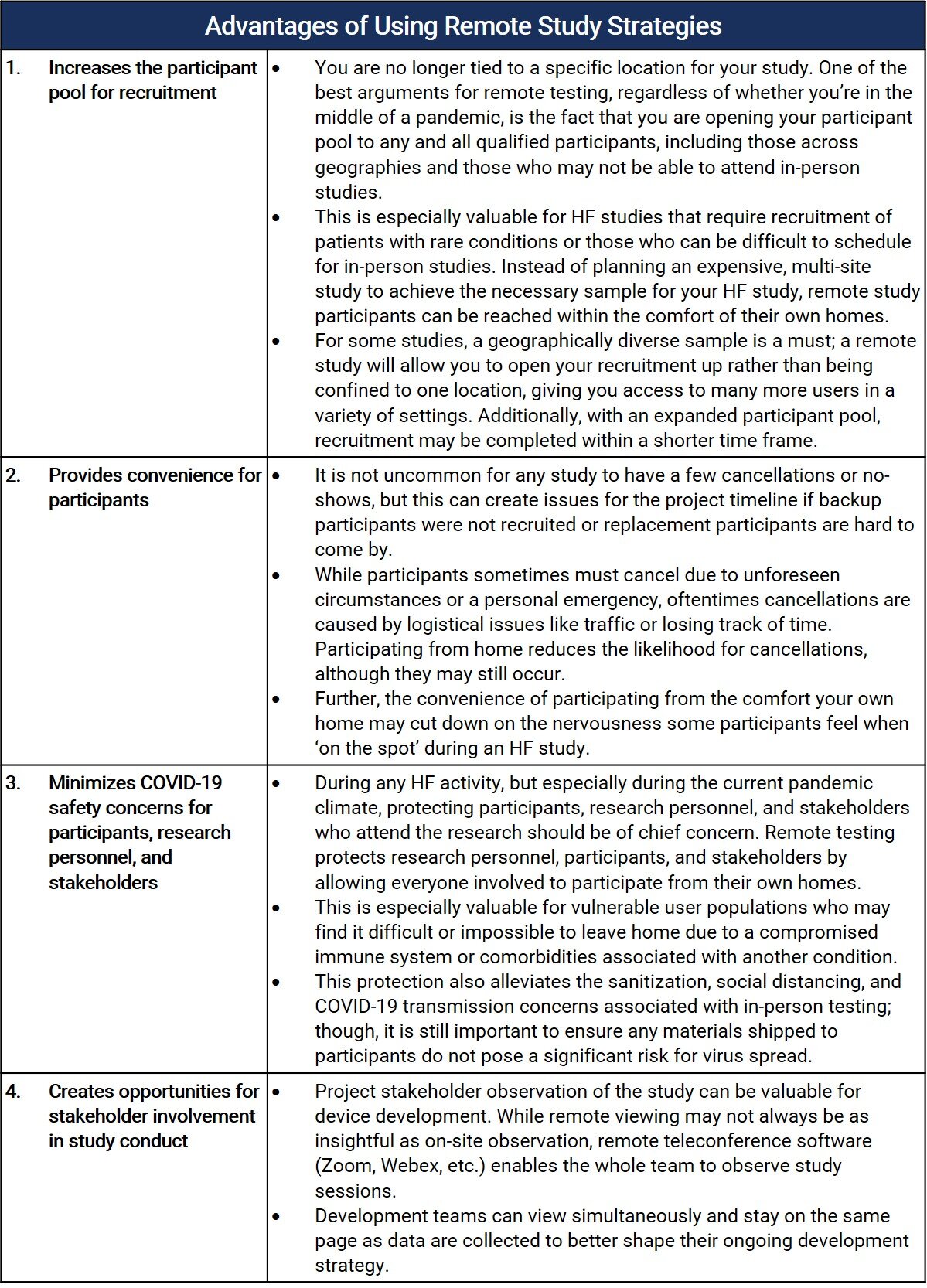

Remote sessions offer several key benefits that may make them an enticing option even outside of the current COVID-19 climate. From-home participation may facilitate recruitment efforts as well as provide respondents with unparalleled convenience and safety. Let’s review some of these advantages:

If it’s so advantageous, why wouldn’t I do a remote HF study?

Contrary to what some may say, remote testing is not always a viable option for many types of devices, and the complex logistics of pulling off a successful remote study may surpass that of an in-person study. The investigational goals of your research should be evaluated against the capabilities of remote testing to determine if the methodology can achieve your goals. Typically, studies that rely on verbal participant feedback as opposed to high fidelity simulated use data may be a better fit for remote testing. Remote testing may be best positioned for early/generative HF research (user preference, cognitive walkthrough, focus groups, etc.), instructional material evaluation, and/or some formative evaluations depending on the goals of the research. In many cases, remote testing will not satisfy the needs of a full validation study. Ideally, critical and non-critical tasks should not be evaluated any differently remotely than they are in person. However, depending on your investigational goals and the study type, you may have to evaluate tasks in different ways. The limitations of remote testing may require some flexibility in how a study objective is met (e.g., using a knowledge task when user performance is not able to be observed through simulated use). However, as product development and HF testing approach the validation end of the spectrum, there is less and less flexibility for how tasks can be tested. The primary difficulty with remote testing, in terms of study design, is the fact that research personnel cannot set up the test environment or manipulate the environment throughout the study. For example, a negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) study might need several manikins with varying levels of simulated bleed-through on their dressings – this type of setup may not be reasonable without study facilitators on-site. To overcome such an obstacle, a large number of study materials/accessories would need to be shipped to each participant which may not be logistically possible and would almost certainly be expensive to the project’s budget. Based on the device’s complexity and the organization’s research goals, if remote testing seems viable/necessary, there are some additional factors that should be considered when planning for a remote study.

Considerations for remote studies

If the next step in your HF timeline includes in-person testing and it is not a viable option, then you may be considering remote testing. Teams thinking about remote testing should take the following into account when making decisions. These important factors are also discussed in more detail below:

Identification of investigational goals

Loss of control over the study stimuli (and, to an extent, the pace of the study)

Recruitment considerations

Study schedule flexibility

Data/video capture methods

Remote testing logistics

The selection of a study methodology is typically based on the investigational goals (i.e., the type and quantity of data desired) of a study. However, in the current pandemic climate, we don’t always have the freedom to select the best-fit methodology and may have to reassess and adjust our investigational goals. For example, if an in-person simulated-use method is the best fit but is not currently possible, a remote test could be used, but it may only be able to generate user input on mock-ups or the IFU only. Two variables should be considered when evaluating the reasonability of your investigational goals for remote testing: device complexity and methodological complexity. Device complexity is based on the elements of the device user interface (UI) and associated use cases, while methodological complexity refers to the study methods necessary to evaluate the UI to satisfy investigational goals. The combination of these will determine if your study may be appropriate to conduct remotely. Let’s consider Study A, where your company wants to conduct a pre-summative study for a robotic system (complex UI) in preparation for a validation study. The investigational goals for such a study require in-person simulated use scenarios in an OR environment, which is not something that can be achieved in a user’s home. On the other hand, let’s consider Study B where your company wants to conduct early formative testing on labeling design concepts for the robotic system. The robotic system has a complex UI, but the investigational goals in Study B focus on one aspect of that UI and makes a remote study a feasible option if an in-person study cannot be conducted.

When making decisions about remote vs. in-person testing, consider all relevant parts of the UI associated with your investigational goals, including any training components. Systems with a significant training component may be at a disadvantage as remote interaction greatly limits the scope of interaction and tutorial a trainer can have with the user. Additionally, remote training may be a concern for programs in which the training is meant to be a validated part of the regulatory submission, as training over web-conference may not represent the commercial training program.

If your company’s investigational goals are to conduct HF validation on a device (regardless of UI complexity), keep in mind that FDA’s CDRH and CDER have stated that any sponsor who is considering a remote testing HF validation study should submit their protocol to FDA for review prior to conducting the study. FDA will review these protocols and issue guidance on a case-by-case basis. Therefore, if sponsors choose to proceed with remote validation studies without FDA’s protocol review, they are doing so at their own risk.

Because research personnel and participants are not co-located during a remote study session, study moderators do not have the same amount of control over the study and stimuli as they would have during in-person studies. If you are considering remote testing, think about:

Intellectual property: Are there intellectual property (IP) concerns related to sending devices and related materials (e.g., IFU) to participants? If so, the control of this IP will need to be entrusted to mail carriers, participants, and sometimes study recruiters (if necessary for the implementation of the remote test). Is this loss of control something that your organization can tolerate? Additionally, there is added risk for no-show participants as they have the materials but may be non-responsive or difficult to reach to arrange return shipment. It may be beneficial to build language into the informed consent and confidentiality forms around the legal implications of disclosing IP or failing to return study materials.

Risks to participants: Will any study materials present a safety concern to participants or members of their household, and is that a risk that sponsors are willing to take (e.g., pen with a real needle or medication, pen with a cap that could be swallowed)? As participants will be remote, moderators are not able to exert the same level of control over the test environment or intervene to prevent harm from occurring. For example, for an in-person study, a moderator may limit the participant’s interaction with hazardous components or ensure that materials are disposed of properly (e.g., autoinjector cap/choking hazard, needle in the sharps container, etc.).

Pace of the study: Additionally, an important piece of the moderator’s duty during an HF evaluation is to set the pace of the study and to provide clear and unbiased instructions for the participant. Something as simple as when the participant sees each UI component can significantly shape their perception of the device or, in the worst case, bias the participant for upcoming tasks. For in-person studies, the moderator can hand participants study stimuli at the point in the session when participants are expected to interact with the stimuli. The pace of a remote study, to some extent, may be able to be controlled by strategic packaging and instructions to the user.

Unforeseen difficulties/interruptions: The participant’s involvement and attention to the study session is dependent on factors outside of the research personnel’s control. Internet connection quality and in-home distractions will vary from participant-to-participant, so the study schedule should be flexible to allow for these potential difficulties. Study sessions may go over time if the participant needs to take the first 15 minutes to get their technical connection figured out or if they need to step away mid-session to help their children with home schooling.

Your recruitment needs for a remote study will vary greatly from a typical in-person study. While the recruiter’s service offerings will be important, it is also key to consider how your methodology may affect your participant sample by inadvertently introducing sampling bias:

Choose the right recruitment partner: One of the advantages of remote testing is the ability to sample participants from a large geographical area (e.g., national search); if this is something that you want to take advantage of, it will be important to contract with a recruitment agency with a database that includes many large markets and can confidently fill your sample while ensuring an adequately diverse participant group. Additionally, it may be important to contract with a recruiter who can help facilitate technological aspects of the remote testing, like providing ‘tech checks’ with participants before their sessions as well as tech support during and after sessions.

Understand that sampling bias is a limitation: While, for the most part, remote testing expands your recruiting reach, there are a few ways in which it might unfairly disadvantage certain users. Because participants must access the study session via technology (e.g., laptop with webcam, internet access) you are inadvertently excluding representative users who do not have access to these technologies. Further, certain populations may find it difficult to use these technologies even if they do have access to them (e.g., elderly people who have trouble with technology). These recruitment limitations may or may not have a significant impact on your study depending on your device’s intended user population(s) and your investigational goals. If the device is specifically targeted at users with low technological access and variable levels of health literacy, then sampling bias associated with remote testing may pose a problem.

Ensure participant confidentiality: Participant confidentiality requires more consideration for a remote test than it would for an in-person test, as participant contact information and mailing addresses will be necessary for the shipment of study materials. How you handle the distribution (or lack thereof) of this information will be especially important if you intend to conduct a blinded study.

Study schedule flexibility is especially important for remote testing. Because study stimuli must be mailed to each participant ahead of time, cancellations and no-shows are much harder to replace and these participants may also have IP that you need to ensure gets returned. Rescheduling these participants is likely to be the most convenient way to ensure the sample size remains intact but may require a flexible schedule that can accommodate their make-up slot (e.g., built in empty slots, willingness to take an early or late session, etc.).

Because you will not be in-person with the participants, you will need to capture their interactions and feedback via a camera and a microphone. Allowing the participant to use their own webcam/microphone is often the simplest solution but can also be challenging because of the variability in technology used by the participants. A participant may have a laptop with an integrated webcam (relatively easy to adjust), an all-in-one desktop with an integrated webcam (very difficult/impossible to adjust), or an external USB webcam (easiest to adjust).

Alternatively, you could send external audio/visual (A/V) equipment to each participant (e.g., a USB webcam, lapel mic, etc.). This would ensure that all participants have the same, high quality A/V collection capabilities but it would increase the technical burden on the participant. Some participants struggle to get their own webcam working; an external solution may exacerbate the problem.

In either case, it can be useful to include detailed instructions for participants (recruiter/tech support may be leveraged here) and maintain a flexible schedule for the participants that may experience difficulty that delays their session.

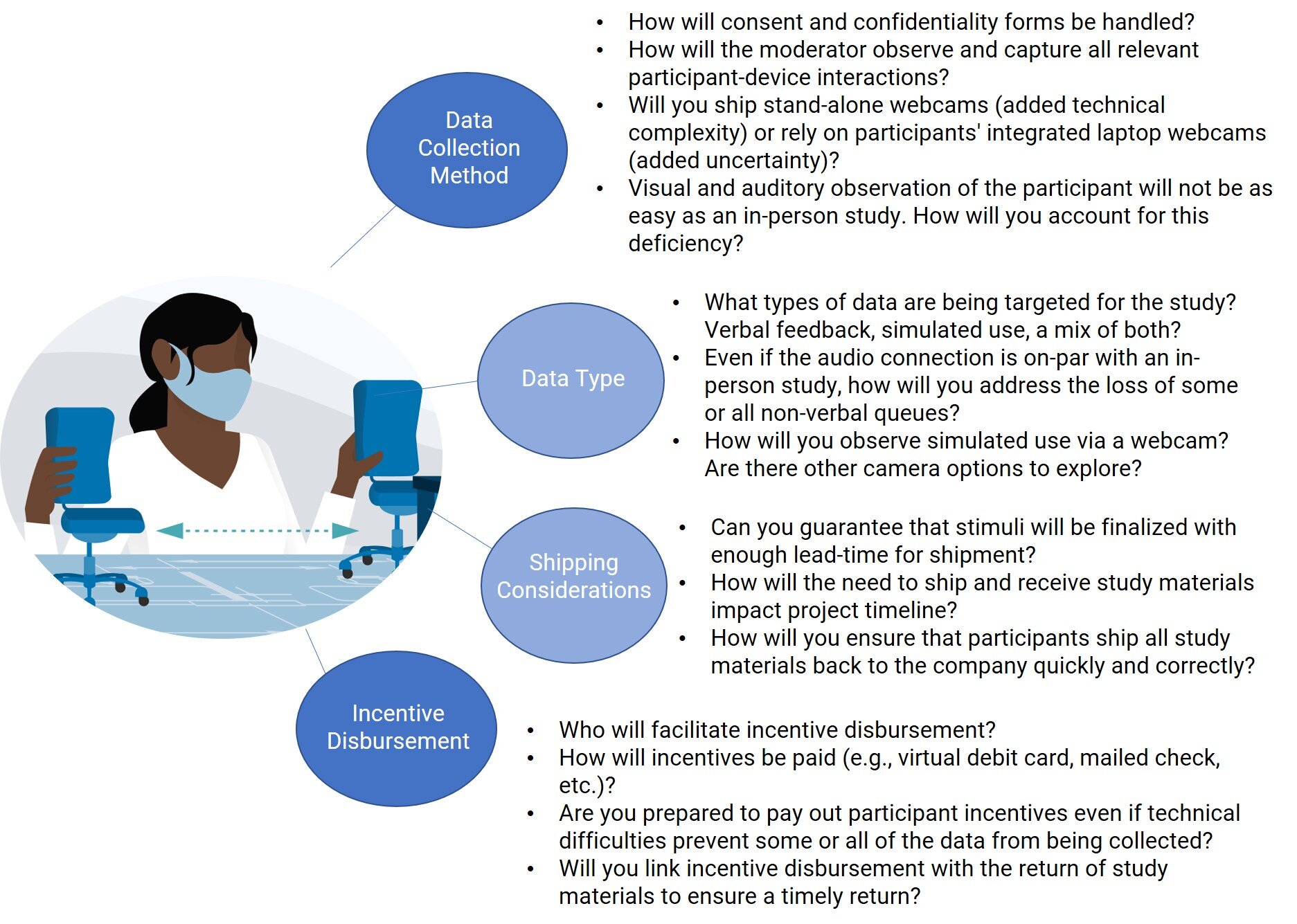

If the above considerations are taken into account and a remote study remains a viable option, there are several logistical aspects that should be considered when preparing to conduct a remote study:

What is the regulatory perspective on remote testing?

Though regulatory bodies have given some guidance for clinical studies during the pandemic, they have held off on offering guidance for HF activities. While CDRH and CDER representatives from the FDA have indicated that a guidance document may be created in the future if the pandemic continues into the new year, the FDA is currently recommending that any remote testing validation protocols should be submitted prior to study conduct and will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis. If a study sponsor opts to forgo this review, they will be conducting the study at their own risk.

What’s in store for the future of HF research?

As we make our way into the fourth quarter, in the light of COVID-19, the future is still uncertain. Many companies have decided not to bring employees back on-location until at least the new year; and even when we do get back into the office, how we do business going forward may never be the same. Lessons learned and experiences gained during the pandemic will shape our business in the years to come. By carrying on and adapting to the pandemic we can bring new proficiencies into our rolodex. Adding to the sentiment of Part 1 of this newsletter, “we encourage you to plan ahead for various scenarios so that your HF programs can keep moving forward” and to take advantage of this opportunity to explore new methodologies and ways of achieving your goals. Agilis has been conducting both in-person and remote studies and can offer expertise and lessons learned to help support your HF program.

Stay tuned for next month’s newsletter when we discuss plans for 2021!

About the Author:

Ryan Hilgers

Ryan Hilgers is a Human Factors Consultant with Agilis Consulting Group, LLC. Ryan comes from 5+ years of industry experience consulting on the design, development, and validation of medical devices. During his career, Ryan has worked on a variety of device types from autoinjectors all the way to surgical robots.

Ryan earned a Bachelor’s degree in Human Factors Psychology from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University (ERAU) before continuing on to a Masters of Science in Human Factors and Systems Engineering which he completed with a thesis titled “Human Factors Contributing to Preventable Adverse Drug Events in Healthcare.”